An essay responding to Joe Moran’s work Its contours, Its movements at APT Gallery in Fest en Fest 2022

Two dancers face each other across a sparsely furnished room. ‘I AM WHAT I AM’ shouts one. ‘My body belongs to me’, the other calls out, to which the first responds, ‘I am me and you are you, and something’s wrong’.[i] Amplified by one voice, then the other, then both voices simultaneously, the “I” of this textual citation announces an individual subject that is quickly undone – unfixed – by a something’s wrong. What exactly is wrong? The citation goes on:

‘Mass personalization. Individualization of all conditions––life, work and misery. Diffuse schizophrenia. Rampant depression. Atomization into fine paranoic particles. Hysterization of contact. The more I want to be me, the more I feel an emptiness. The more I express myself, the more I am drained. The more I run after myself, the more tired I get’. [ii]

There can be too much self under capitalism, The Invisible Committee, who authored this quotation, seem to suggest – a too much of not enough. Thomas Heyes strides over to Temi Ajose-Cutting as they continue the citation. And as the dancers make contact and tussle, the anxious inner voice whose double is that vocalised “I” carries over to their contact, becomes a question of contact, and the limits of ‘my’ boundary are no longer assured.

Expanded choreography involves the unfixing of boundary through the exposure of boundary to a constitutive outside that undoes it, repeatedly.Expanded choreography sometimes involves dancing. Often it doesn’t.

Writers like Bojana Kunst and André Lepecki argue that contemporary performance is disruptive because it mediates the symptomology of life under capitalism. In their writing, corporeal states like stillness, silence, vibration, jitteriness, and tensegrity that are ubiquitous in contemporary performance reiterate the psychic experience of ‘life, work and misery’ – with a difference. The effect of this reiteration is twofold: it expresses the something’s wrong of individual freedom and frees the individual from the violence of boundary, queerly.

Expanded choreography sometimes involves contemporary performance. Often it doesn’t.

A boundary is more than one thing is the phrase that comes to mind when reflecting on the work of Joe Moran, whose practice to date involves choreography, dance, drawing, sculpture, film, and collaboration, among other things. This essay forms a response to Moran’s expanded choreography as it pertains to his drawing practice; at the same time, my essay is a study of boundary that is guided by the question, how does a boundary materialise? And further, what is the relationship between boundary and expanded choreography?

—

Moran’s film Materiality Will Be Rethought (2020), with which this essay opens, deals with boundaries. Made during the first Covid-19 lockdown, when boundaries proliferated through the measure of social distancing, Materiality Will Be Rethought was sited at the Whitechapel Gallery in dialogue with Something Necessary and Useful, an installation by Portuguese artist Carlos Bunga comprised of movable architectural forms rendered in cardboard, restored furniture, and hand tools that cite the Shakers – an 18th Century millenarian sect remembered for their utilitarian lifestyle and ecstatic worship. Over the course of the 30-minute film, four dancers – Ajose-Cutting and Heyes; Eve Stainton, and Sean Murray – traverse the space. As they interact in and around Bunga’s constructed and found objects, they step in and out of exhibition time, shifting between object-like, tensile, and fluid modes of engagement, agitating boundaries.

Dancers become object akin to objects in the surround, might name a trope of expanded choreography. I think of choreographer Maria Hassabi’s deployment of transition and threshold in PLASTIC, her 2016 MoMA commission – startled, we see the gallery-goer automatically steps sideways to avoid stepping on the performer who lies prone on the stairwell. The dancers in Materiality Will Be Rethought pursue an altogether different strategy, however, as their objectlike propensities involve more than one performer: one supports one, or two support one, in deconstructing vocal, corporeal, and kinaesthetic boundaries.

The film involves a series of durational assemblages and marked transitions, as the four dancers variously activate or fuse with objects in the surround. Moran’s strategy of more than one produces contrary effects. For instance, one dancer lies on the back of another, inverting their crawling position, until they are met by a third dancer, who combines with them to produce a triple-bodied cylindrical form that rolls next to the furniture like a rickety carriage wheel. Or else three dancers lie stacked on a chest of drawers, and then the floor, like a set of pallets set aside for future use. These bounded polymorphous objects represent a slippage into exhibition time, albeit one that is frequently mitigated by choreographic interruptions: synchronised lunges, scissor-kick jumps, line patterns, and that gorgeous Nijinsky pose from L’Après-midi d’un faune (1912) each serve to re-establish theatrical time and choreography as the subject of the work. Materiality Will Be Rethought thus flickers between exhibition- and theatrical time.

Otherwise, the dancers are involved in an examination of architectural space, as illustrated by the following four examples: 1) Two dancers, one standing on the shoulders of the other, slowly circumnavigate the parameter of Bunga’s installation, pressing their hands against the wall as if searching for hidden cavities, and carefully manoeuvring around chairs that have been left hanging from wooden pegs – a reference to the migrants who used the space of the installation, which was formerly a local library; 2) Four dancers stand nestled in the cavities of Bunga’s cardboard walls, backs to the camera – the effect of their becoming wall recalls SERAFINE1369’s exhibition ‘We Can No Longer Deny Ourselves’ at Somerset House Studios (2022), when, at one point, Jamila Johnson-Small faced the wall obdurately for several minutes. In one frontal shot, Stainton and Murray are installed in adjacent cavities that are segmented by a vertical gap, forming a body that appears cut in two like an exquisite corpse; 3) Four dancers shroud themselves in voluminous grey dust sheets, standing in a circle and, later, lying together in a clump that assumes the appearance of a vast stolid rock, recalling Ingri Fiksdal’s Diorama (2017-); 4) The film ends with the lone figure of Heyes repeatedly kicking the brick wall, a futile gesture that reminds me of Yvonne Rainer’s reflection on her recent choreography:

Almost unconsciously, I gravitate toward material that, outside of its sheer rowdy exhibitionism, taps into our complicity in the enjoyment of transgressive behavior, and men are often the ones who manifest this behavior most powerfully. However, the performance of this macho posturing in my dance may or may not suggest the vainglory of war or, for that matter, rage at poverty and racial inequities, challenge to authority, fuck you, in a word — transgression. Angry young men’s gestures may be “regressive,” according to friend Simon, but as embodied in my dancers’ imitations, they become something else. Here they constitute part of a continuum of choreographic possibilities, a gamut of affects that, as in the democratic organization of components in Trio A, foregrounds the performer performing, the self receding, and the passion hiding, in plain sight.[iii]

Rainer’s quotation speaks to a third concern of Materiality Will Be Rethought, representation. Her point is that transgressive behaviour, exemplified by ‘macho posturing’, is useful choreographically because its deployment, when juxtaposed with other affects and movement possibilities, foregrounds ‘the performer performing, the self receding, and the passion hiding, in plain sight’ (I love this phrase). Masculinity in performance – Heyes’ futile kicking – represents the possibility of an escape from the toxicity of representation through its unfixing and tethering to choreographic possibilities, an escape that could be said to parallel or even, through its performative edge, exceed the possibilities of theoretical exposition. For my purposes, Rainer’s musing is helpful because it picks up on a set of interlocking concerns – masculinity, choreography as ‘form subject discipline’, deconstruction, and perceptual practice – that guide Moran’s work to date and find new form in Materiality Will Be Rethought.

The title of Moran’s film, Materiality Will Be Rethought, is taken from the Introduction of Judith Butler’s monograph, Bodies That Matter: On the discursive limits of “sex” (1996). This passage was selected by queer historian Paul Halferty for Moran’s Texts for Scores for Performance (2010), an ‘open source booklet for inquiry, making, and performance’ that collated selected passages from invited choreographers, makers, and scholars. Texts for Scores’ pragmatic title raises the question: How might Butler’s study of boundary serve a project of expanded choreography?

Bodies That Matter was written in part as a response to mis-readings of Butler’s previous book, Gender Trouble (1990). In its opening pages, the author argues against the idea that gender is constructed by an exterior agency that precedes the individual subject. In their view, “sex” materialises through the reiterative practice of regulatory norms, norms that are the price of cultural intelligibility within the heterosexual matrix. Crucially, these norms are reiterative, meaning they do not appear outside of their materialization and material effects. Further, such norms depend on a ‘constitutive outside’, a zone of all that is socially excluded, queer, marginal, or abject – hence the paranoid need to maintain these norms at all costs, a need that is forever haunted by that outside from within. As Butler writes, ‘These excluded sites come to bound the “human” as its constitutive outside, and to haunt those boundaries as the persistent possibility of their disruption and rearticulation’.[iv] Moran’s practice is committed to such disruption, and the choreographic work that leads to Materiality Will Be Rethought charts an inquiry into the possibilities of unfixity.

I want to briefly mention three works by Moran in this connection: Decommission (2008-), Singular (2011-), and Arrangement (2014-). Decommission is a solo that, sometimes performed with Arrangement, draws the audience into its matrix. At its crux, the performer lies still with their back to the audience for four minutes, through which duration they are intensively involved in the perceptual work of disintegrating into earth. The boundary between self and other, human and environment, is unfixed, as the performer draws the audience into a concentrated kind of shape-shifting activity. Singular involves two performers who are tasked with the following instruction: to channel a ‘single consciousness embodied in more than one form’. The two performers are not subjugated but invited to complicate the body through a radical immersion in choreographic scoring that articulates dance as a field of multiplicities. Moran produced the score as a sound installation, shared separately, whose mode of address reminds me of choreographer Deborah Hay’s invitation: ‘What if every cell in my body at once has the potential to perceive beauty and to surrender to beauty simultaneously, each and every moment?’[v] This composability is brought into dialogue with the social in Arrangement, a choreography for six male performers that explores masculinity and queerness. In Arrangement, the performers complicate body and physicalise voice through polymorphous arrangements that cite dance pieces ranging from Simone Forti’s Huddle (1961) to Xavier Le Roy’s Self Unfinished (1998). Arrangement often elicits laughter from the audience: Could this laughter be a sign of masculinity’s ‘constitutive outside’ passing over into the choreographer’s ‘gamut of affects’?

I now bring Moran’s dance works into dialogue with his drawing practice – crucially, both forms fall under the designation ‘expanded choreography’.

—

Its contours, Its movements is an exhibition of Moran’s drawings, film, and performance, at APT Gallery, London, presented as part of Fest en Fest 2022, an international festival of expanded choreography.

This exhibition title and that of Moran’s film Materiality Will Be Rethought cite the same sentence in Butler’s Bodies That Matter, as follows: ‘In this sense, what constitutes the fixity of the body, its contours, its movements, will be fully material, but materiality will be rethought as the effect of power, as power’s most productive effect’.[vi] Again, Butler describes the paradox whereby the body only becomes visible through the reiteration of norms that materialise its effects. The two phrases selected as titles by Moran thus refer to the body as a site of power, one whose significance is registered in the social flux of the contour–movement–materiality that bounds it. Once we posit the body in relation to its material boundary, then it’s a short step to suggest that boundary itself might become the site of contestation for expanded choreography, a site that unfixes representation by positing boundary as more than one thing.

Conventionally, dance troubles the representation of “sex” and gender by the sheer fact of its disappearance, by promising a coherent subject that continuously escapes the viewer.[vii] So far, we have observed strategies by which Moran unfixes boundary in dance, through complicating the body, physicalising voice, and perceptual scoring – yet in each case, boundary is ultimately fixed by the positionality of the dancers involved. Expanded choreography, which sometimes involves dancing though not always, might be said to trouble representation through its materialisation of boundary as that which materialises the human subject. This is where I locate Moran’s drawing practice.

Moran’s first exhibition of drawings, Tracks and Lines (2015) at Gallery Lejeune, London, presented a series of line drawings, mappings, instructions, scores, and figures that engage with a genealogy of contemporary dance. Indeed, choreographers such as Trisha Brown, Simone Forti, Deborah Hay, and Yvonne Rainer have variously utilised drawing to extend their practice, whether as a form of kinaesthetic awareness, mathematical proposition, or choreographic score, and exhibited these in a range of formats. Rendered with felt-tip, graphite, and charcoal among other implements, the drawings in Moran’s Tracks and Lines are not large. They involve the viewer in a conceptual game of parsing grammars and vocabularies, as each drawing encodes movement differently. The drawings retain the propositional character of documents. As Carrie Noland writes of Henri Michaux’s calligraphy, these drawings transmit a ‘kinetic desire’ that is co-extensive with choreography as an expanded field of movement possibilities.[viii] Choreographic procedures are denoted in this series of drawings by number, arrows, line, shape, and colour, as well as forms of layering – compositional elements that conceptually enmesh them with the translation of perceptual activity in the dance studio.

The drawings do not mimetically represent movement, then; rather, they picture choreographic procedure as that which organises and disciplines movement while simultaneously exceeding choreography through their blatant multiplicity. Indeed, they stimulate all kinds of perceptual activity, the coordination of line, edge, and shape reproducing the antagonistic relationship between movement and boundary that forms the core of Moran’s choreographic practice. Separated from the visual field of sexual difference that permeates dance, the drawings in Tracks and Lines expose boundaries to, in Butler’s words, ‘the persistent possibility of their disruption and rearticulation’. To the extent that these drawings are linked to the choreographic, they involve the viewer in the conceptual study of movement.

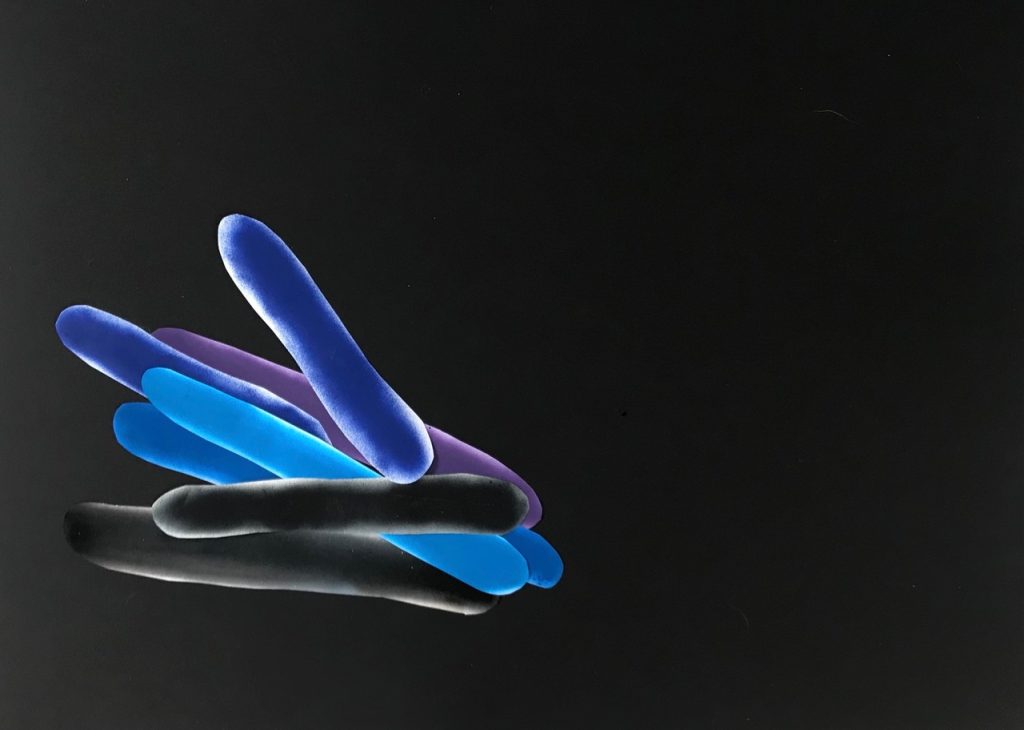

The current exhibition, Its contours, Its movements, includes an autonomous body of spray-paint drawings that are distinct from the documentation of choreographic procedure. Moran fortuitously discovered a set of spray-paint cans while participating in a 2018 residency at Launch Pad LaB, in rural France, and began to experiment with their application to different surfaces. Through these early attempts, he alighted on a motif that has remained consistent throughout the spray-paint drawings: a colourful strip with rounded edges that roughly equates to an oblong. This oblong-like motif connotes organic matter ranging in scale from cellular forms, parasites, and villi to limbs and bodies. Crucially, though, this motif is non-representational: the oblong does not mimetically “stand for” a body. Nonetheless, the spray-paint’s weightless, almost Apollonian quality is perceptually linked to the ephemerality of the dancer, whereby the viewer is caught in a loop of verifying the substance of that which is always on the verge of escaping. Precisely for this reason, perhaps, the spray-paint drawings are primarily a study in boundary, border, edge, limit, and their attendant modes of dependency, relationality, and collectivity, where boundary, we could say, stands for an active resistance to the racialised character of an aesthetics of transcendence (read: white supremacy) – a politics of resistance that informs Moran’s practice more broadly.

To consider the spray-paint drawings a study of boundary is, with Butler, to read these works in relation to the materialisation of the effects of power. In this final section, I track the permutation of boundary across the spray-paint drawings to arrive at concluding thoughts about Moran’s expanded choreography.

—

The first large-scale spray-paint drawings comprise a mass of oblongs in shades of red, blue, green, and black. Each oblong is encased in a loose and irregular felt-tip line that doubles back on itself at the short ends of the shape, so that each oblong is idiosyncratic and full of character. This set is decidedly process-oriented and resonates with the choreographic drawings included in the earlier exhibition, Tracks and Lines. Jettisoning the idiosyncratic line and its gestural energy, Moran’s next innovation was to cut out the spray-paint oblongs so that each one now comprised a precise, full-bleed edge. This action marked a definite break from the earlier drawings, delineating the oblong as an autonomous form. He then experimented with layering these self-standing motifs against neutral supports, organising them into different orientations and compositional arrangements.

In one drawing, a group of six oblongs in blue, black, and purple are assembled in a kind of stack or pile in the bottom-left quadrant of a large piece of black paper. This pile of oblongs resembles the queer pile of six men in Moran’s choreographic work, Arrangement, as well as the stacking of performers in Materiality Will Be Rethought, mentioned above. Crucially, however, the resemblance is not constrained by the field of representation. Qualities of conceptual choreography such as stillness and duration, that Moran has actively explored in relation to the project of ‘exhausting dance’ as inaugurated by André Lepecki, return here via an insistent form of perceptual oscillation, or vibration.[ix] The boundary of each oblong is both blatantly evident and impossible to fix, a hiding in plain sight that refuses the linear finality of time and seems to “get at” the experience of life under capitalism. (Though there’s a final trap, as it’s impossible not to read the colours black, blue, and purple culturally). In a second drawing of a similar format, two discrete piles of oblongs confront each other on the black background (and there again, it’s difficult to avoid turning to figurative, psychic metaphors). On the left side, eight oblongs are arranged horizontally while on the right, three neon-green oblongs are grouped vertically. This stark dyad has all the conflictual drama of a pas de deux, and for this, it raises the possibility that the regulatory norms that materialise the ‘dyadic differentiation within the heterosexual matrix’, as Butler puts it, risk returning.[x] And yet my gaze keeps returning to boundary, contour, edge, to the queer ‘constitutive outside’ that their materialisation implies, suggesting a conceptual step beyond representation.

In the final permutation to be considered here, Moran applies the oblong motif to white tiles, a regular, combinatory format that can be disassembled and reconfigured. For the exhibition Its contours, Its movements, the tiles are arranged in two horizontal layers at the foot and top of a bench-like structure. This drawing, which literally extends into the gallery space, intervenes architecturally to materialise boundary as that which implicates the body of the viewer. As Robert Morris wrote in his important 1966 essay, “Notes on Sculpture, Part Two”, ‘The awareness of scale is a function of the comparison made between that constant, one’s body size, and the object’.[xi] Where Morris pushed the object’s autonomy to the point that it became a feature of architectural space, Moran’s spray-paint tile drawing remains distinct as it still occupies pictorial space. Moreover, the boundary of each oblong has here been inverted using the cut-out, with spray-paint serving to define the shape negatively as a silhouette, a reversal that generates a centrifugal force that means the oblongs appear to float in relation to one another, unfixed yet stabilised through a mutual dependency.

This final permutation reminds me of Candy Works (1990-), a sculptural series by the Cuban-American artist Felix Gonzales-Torres (1957-96). In each iteration of this work, the gallery audience were invited to take a candy from a spill of wrapped candies, and the pile would be replenished at the end of each working day to match a perfect weight determined in advance. One of these spills, “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) (1991), weighed 175 pounds, the weight of Gonzales-Torres’ boyfriend Ross Laycock when he died of complications from AIDS.

—

Expanded choreography involves the unfixing of boundary through the exposure of boundary to a constitutive outside that undoes it, queerly.

Moran’s dance and drawing works form a continuous inquiry into the unfixing of boundary, albeit by different means. In the dance works, the body is always more than one, while in the drawings works, boundary is materialised forcibly against the shadow of representation – and again, the distinction between dancing and drawing begins to break down.

Tom Hastings

November 2022

[i] Invisible Committee, Coming Insurrection, Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2009, p. 29.

[ii] Invisible Committee, Coming Insurrection, p. 29.

[iii] Yvonne Rainer, Where’s the Passion? Where’s the Politics? Or, How I Became Interested in Impersonating, Approximating, and End Running around My Selves and Others’, and Where Do I Look When You’re Looking at Me?, Theater, 2010, 40: 1, p. 54.

[iv] Judith Butler, Bodies That Matter: On the discursive limits of “sex”, London: Routledge, 1996, p. xvii.

[v] Deborah Hay, Using the Sky: A Dance, London: Routledge, 2005, p. 17.

[vi] Judith Butler, Bodies That Matter, p. xii.

[vii] See Peggy Phelan, Unmarked: The politics of performance, London: Routledge, 1993. NB: Phelan’s account generated fierce critical debate, yet her arguments remain foundational in the field of performance studies.

[viii] Carrie Noland, Agency and Embodiment: Performing Gestures/Producing Culture, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009, p. 147.

[ix] André Lepecki, Exhausting Dance: Performance and the Politics of Movement, London: Routledge, 2005.

[x] Judith Butler, Bodies That Matter, p. xx.

[xi] Robert Morris, “Notes on Sculpture, Part Two”, Artforum, Vol. 5, no. 2, October 1966, p. 231. NB: It does not seem accidental that Moran’s spray-paint drawings on tile fit in a genealogy of minimalist sculpture that served to advance postmodern dance; there are grounds for further research into sculpture and dance in Moran’s practice, and the work of his peers, that falls beyond the scope of this essay.

Tom Hastings is a Lecturer in Dance at London Contemporary Dance School. Tom lectures on contemporary dance at the intersection of critical race, postcolonial, Marxist, feminist, and queer interventions. He works across BA/MA, encouraging students to approach their dance practice as a mode of live research. Having studied Literature (BA; UCL) and Critical Theory (MA; Sussex), Tom completed his PhD in Art History at University of Leeds in 2018 – his thesis, “Defining the Body-Object of Minimalism: Yvonne Rainer and the 1960s”, explores the relationship between writing, movement, and props in Rainer’s expanded choreography. At present, Tom is co-editing a volume of essays titled Feminist Genealogies of the Body and gathering material for a book proposal through teaching; his first monograph, Johnnie Cooper: Sunset Strip, was published by Black Dog Press in 2018. Peer-review articles feature in Platform: Journal of Theatre and Performing Arts, Sculpture Journal and Performance Research; art criticism in Artforum, Art Monthly, Frieze, Burlington Contemporary, Studio International, Ma Bibliothèque, and Texte zur Kunst. Tom is a former Co-Editor of parallaxjournal (2015-18) and is at work on a book to do with gesture politics.

Its contours, Its movements is a two-day exhibition by artist and choreographer Joe Moran bringing together a new configuration of film, spray paint drawings and performance together navigating notions of disruption, complication and unfixity, part of Fest en Fest 2022, festival of expanded choreography.

Essay commissioned by Dance Art Foundation to accompany the exhibition Its contours, Its movements by Joe Moran for Fest en Fest 2022